‘How Are the Schools?’ Home Values, Property Taxes, and Education Inequality

- Published on

- 8 min read

-

Chelsea Levinson Contributing AuthorCloseChelsea Levinson Contributing Author

Chelsea Levinson, JD, is an award-winning content creator and multimedia storyteller with more than a decade of experience. She has created content for some of the world’s most recognizable brands and media companies, including Bank of America, Vox, Comcast, AOL, State Farm Insurance, PBS, Delta Air Lines, Huffington Post, H&R Block and more. She has expertise in mortgage, real estate, personal finance, law and policy.

“So, how are the schools?” It’s one of the hottest questions in real estate, and it also happens to be one of the industry’s biggest hot-button issues because it hits at the heart of how schools, taxes, and real estate intersect.

Neighborhoods with high-scoring schools are considered more desirable, and homes in those areas fetch higher prices. Makes sense, right? Many American parents will go to great lengths to give their kids any possible advantage, and that includes paying a premium to live near top schools.

But what are “great schools,” anyway, and how did they get that way? Who gets to have access to America’s best schools, and who gets left behind?

To answer these questions, we need to take a deep dive into the connection between school quality, home values, and property taxes. Here’s what homebuyers need to know.

How are schools funded? The connection between schools, taxes, and real estate

U.S. schools are funded in a few different ways.

First, there’s federal funding for all public schools. The U.S. government sets certain educational requirements that schools have to meet, and it contributes money to public schools so they can reach those goals.

Note, however, that the U.S. Constitution leaves the burden of schooling K through 12th grade primarily on states and municipalities — the federal government contributes around 8% to the average school budget.

States also contribute funding to public schools, though the level of aid varies depending on the state.

Finally, municipalities kick in the rest of the money to fund public schools, and one big way they do this is through property taxes. In fact, research finds that nearly half of all funding for schools in the U.S. is generated by local taxes.

Property taxes are based on assessed home values, and values vary widely from town to town. That means ultimately, wealthy towns are able to put significantly more money into their schools than low-income towns. Further, towns with more businesses often collect more taxes and then are able to funnel some of that money into schools.

Across the U.S., the average high-poverty district spends 15.6% less per student than the average low-poverty district. But in some states, the rift can be much larger. For example, in Pennsylvania, that gap is more like 33%.

“Small districts can have the effect of concentrating resources and amplifying political power,” shares a recent report by EdBuild.

“Because schools rely heavily on local taxes, drawing borders around small, wealthy communities benefits the few at the detriment of the many.”

The school funding system provides advantages for children attending school in wealthier school districts, and it also perpetuates disadvantages for children in lower-income areas. School inequality can result in poor outcomes for those low-income students, thus perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

And of course, this system disproportionately disadvantages students of color, especially Black and Latino children.

The great school funding divide

There’s a huge divide in school funding across the U.S., but the divide isn’t just about wealth; it’s also very much about race. Recent research by EdBuild found that white schools get $23 billion more in funding than non-white schools, even though they serve the same number of students.

“Students in poor nonwhite districts receive substantially less money than even their poor white peers, despite years of court rulings intended to create a level playing field for all students,” the report reads.

Let’s take a look at some school funding numbers:

- The average white school district receives $13,908 in funding per student.

- High-poverty white districts: average $12,987 per student.

- Low-poverty white districts: average $14,121 per student.

- The average non-white school district receives $11,682 in funding per student.

- High-poverty non-white districts: average $11,500 in funding per student.

- Low-poverty non-white districts: average $12,205 in funding per student.

That means the average white school district receives $2,226 more per student than the average non-white district. And even in low-income white school districts, each student gets $782 more in funding than students in wealthier non-white districts.

Compounding the inequality is the fact that white districts tend to enroll fewer students. The average white school district enrolls around 1,500 students, while the average non-white school district enrolls more than 10,000 students.

Having both more money and fewer students is a powerful combination, with distinct advantages for certain families.

“‘Local control’ of taxes benefits only the privileged few — small white districts created by arbitrary lines that can raise unfettered money for their schools,” EdBuild explains. “As a general rule, states haven’t kept up with the gaps created by an inherently unequal distribution of wealth in a racially fractured society.”

The bottom line: School districts that are predominantly white get more funding per student overall, regardless of income levels. Meanwhile, non-white schools are at a major funding disadvantage.

Segregated schools

Let’s indulge in a little history lesson. For much of U.S. history, schools were segregated by law, meaning white students and Black students were forced to learn separately.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated, so-called “separate-but-equal” educations were unconstitutional in the landmark decision Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka. This ruling ended forced segregation. In a separate ruling in 1955, Brown II, the Supreme Court urged the U.S. to desegregate schools with “all deliberate speed.”

Unsurprisingly, however, desegregation efforts didn’t happen overnight.

“Instead, white parents left for the suburbs, created Christian schools, formed White Citizens’ Councils and filed lawsuits,” explains Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, author of The Voting Rights War and professor of constitutional law at John Jay College (CUNY). “Virginia even closed its public schools to avoid desegregation.”

One important policy that helped desegregate schools in the wake of Brown was busing, a practice that was protected by the Supreme Court in 1971. Busing meant bringing students — typically Black students — into white school districts to create more integration.

Busing and other integration efforts persisted for decades and showed some really promising outcomes. In fact, decades of studies show that integration has positive outcomes for students of all races (more on those benefits later).

But many white families didn’t see it that way and continued to bring anti-integration cases to the courts, arguing that forcing integration was discriminating against white students.

The courts, in turn, have all but upended desegregation efforts. For example, a 1999 case ended court-ordered busing, and by 2007 the Supreme Court ruled that even voluntary busing amounted to discrimination against white students, putting the final nail in the coffin on decades of school desegregation efforts.

Today, it’s considered unconstitutional for schools to make race-based student enrollment plans meant to achieve integration.

So just how segregated are America’s schools since Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka?

It turns out, the U.S. as a whole is nearly as segregated as it was 50 years ago, and school segregation is now getting worse.

Recent research reveals that more than half of America’s children attend school in racially concentrated districts, meaning 75% or more of the students in a school are of the same race. Another study found that around one in five public schools has almost no non-white students.

“The racial and economic segregation created by gerrymandered school district boundaries continues to divide our communities and rob our nation’s children of fundamental freedoms and opportunity,” Edbuild explains.

They go on: “Families with money or status can retain both by drawing and upholding invisible lines. Many families do just that. This, in conjunction with housing segregation, ensures that — rather than a partial remedy — district geographies serve to further entrench society’s deep divisions of opportunity.”

Home values in segregated neighborhoods

One big thing that plays into school funding: property taxes. And how are property taxes assigned? They’re determined by home values.

Home values in non-white neighborhoods are lower and appreciate much less quickly than homes in white neighborhoods.

A recent Brookings Institution report found that “in the average U.S. metropolitan area, homes in neighborhoods where the share of the population is 50 percent black are valued at roughly half the price as homes in neighborhoods with no black residents.”

The report further explains: “Homes of similar quality in neighborhoods with similar amenities are worth 23 percent less ($48,000 per home on average, amounting to $156 billion in cumulative losses) in majority-black neighborhoods, compared to those with very few or no black residents.”

Further, the Black neighborhoods that suffer this property devaluation are more segregated, and the children who live in them have far less upward mobility.

The devaluation of Black property has huge consequences for schools that rely on property values — and their ensuing tax dollars — to provide funding for students. With municipalities contributing up to half of school budgets, lowered property values mean far less money is funneled into Black schools compared with white schools.

Black-owned homes see less appreciation

Homes in Black neighborhoods appreciate less quickly — if they appreciate in value at all. In most cities, homes in Black-owned neighborhoods actually depreciate in value, even as home values appreciate nationally.

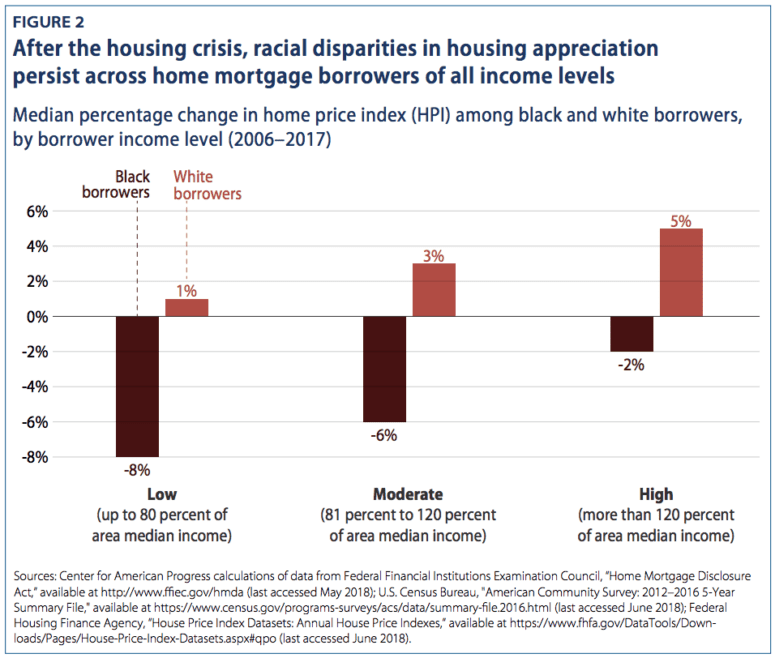

A recent study by the American Center for Progress found that “racial disparities in home appreciation have persisted nationally even in the aftermath of the Great Recession, despite a general increase in home prices.”

The study continues: “In 2017, home prices in neighborhoods where black borrowers have concentrated since 2013 were 6 percent lower than in 2006. Home prices in census tracts attracting white homeowners, in contrast, have increased by 3 percent.”

These findings held true even after controlling for borrowers’ income levels.

“As homebuyers tend to look for housing options in communities where they anticipate greater capital gains, discrimination and low housing appreciation disproportionately harm largely black neighborhoods,” the study concludes.

How does school funding affect test scores?

School funding can have big effects on test scores. Namely, the more money a school district has, the better it tends to perform on tests.

For example, in the richest school districts, research shows that sixth-grade students are roughly four grade levels ahead of students in the poorest districts.

A massive National Bureau of Economic Research education study found that more school funding consistently results in better outcomes for students, including higher test scores, better graduation rates, and the potential for increased earnings later on in life.

A study out of Texas similarly found that an extra $1,000 of funding per student raised test scores, lowered dropout rates by 2%, increased college enrollment by 9%, and improved the college graduation rate by 4%. The results were even more pronounced in areas of high poverty.

Another recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that a 20% increase in spending per low-income student can result in an additional year of education, 25% higher earnings, and a 20% reduction in annual incidences of poverty.

These positive educational outcomes can have long-standing positives for low-income families and can help pull families out of generational poverty.

The benefits of integrated learning

Increased spending isn’t the only way to improve educational outcomes. It’s been long understood that integrated learning has distinct benefits for students of all races, but we’re still uncovering just how multifaceted and widespread these benefits are.

Recent research by the Century Foundation found students in diverse classrooms enjoy a wide range of benefits:

- Higher test scores

- More likely to enroll in college

- Less likely to drop out of school

- Reduced racial achievement gaps

- Stronger critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity

- Reduced racial intolerance and bias

- More likely to seek out integrated spaces later in life

- Improved student satisfaction and greater self-confidence in academic abilities

- Enhanced leadership skills

- Meaningful relationships between students of different races

- Reduced anxiety

- Integration efforts offer a high return on investment for school systems

- More equitable access to resources

- Students are more prepared to succeed in a global economy

- More productive, efficient, and creative teams

- Higher earnings as adults

- Improved health outcomes

- Students are less likely to be incarcerated

Looking for solutions to school segregation

The increasing segregation of schools is creating a unique problem for districts to solve: How do they integrate and improve outcomes when they can’t make race-based integration plans?

To that end, a few school districts around the nation have created innovative models that could offer some potential solutions to this sticky problem.

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, the school system is now a “controlled choice” system. Neighborhood schools don’t exist, and every school in this district has a mix of high- and low-income students that reflect the makeup of the community.

In San Antonio, Texas, they’re opening high-quality, specialized schools that will attract students from all walks of life. The schools strive to balance the student body by socioeconomic status. Their plan has already seen huge improvements in student performance, and the number of overall students attending low performing schools dropped from 47% to just 16%.

New York City, known as one of the most segregated school systems in the country, is now changing its ways. Some of the city’s most affluent districts are now running lottery systems for schools, allowing more diverse students in and busing more affluent students out.

Another model that’s recently popped up to help improve education for Black students in low-income neighborhoods? Afrocentric schools.

These schools are run primarily by people of color and are race-affirming for Black students. They teach Black history, celebrate Black bodies, and improve self-esteem for Black students. They also tend to have higher graduation rates and standardized test scores than city averages.

Industry-wide reform is needed

While it’s important for cities to take a hard look at the segregation in their schools, the issues of disparate real estate values, property taxes, and schools are about more than school integration.

They’re also about the real estate industry as a whole — real estate agents steering buyers, discriminatory mortgage lending, home appraisal bias, the long-standing effects of redlining, and persisting white flight, among other contributing factors.

Until the industry works to solve the structural imbalances for non-white homeowners, these disparities will continue to exist.

Header Image Source: (Cynthia Farmer / ShutterStock)